AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Must read:

LIVING BEYOND TERRORISM: ISRAELI STORIES OF HOPE AND HEALING

Follow Zieva Konvisser’s blog on The Times of Israel website

Follow Zieva Konvisser’s blog on The Israel Forever Foundation website

-

How did the idea for your research and subsequent book originate?

My interest in terror survivors in Israel began years ago as I heard the extraordinary stories of survivors of the Holocaust, in particular those few members of my own family who had survived. More than thirty of my relatives – my grandmother’s parents, brothers and sisters and their families, as well as six of my grandfather’s seven brothers and sisters and their families, and numerous cousins – were murdered in Vilna, in what is now Lithuania.

Most of my family members who survived left Europe for Palestine or the United States in the early 1930’s, including my mother’s parents who were ardent Zionists and moved to Jerusalem with their three children.

A few cousins remained behind and lived to tell their stories. Sima Shmerkovitz Skurkovitz, as a seventeen-year old girl, lived through the hell of the Vilna Ghetto and Nazi concentration camps but managed to survive without losing her humanity. Her singing gave hope to her companions in the terrible darkness of the Nazi Holocaust.

Izaak Wirszup, his wife Pera, and her daughter Marina also survived the Holocaust. Izaak lived through the Vilna Ghetto and the camps and came out believing that he was spared in order to make a difference. He encouraged me and others to “try for the maximum.” Out of their struggle came a survivor’s love of life. Izaak expressed it this way: “We have seen how love, friendship, and help can transform the most fragile souls into individuals stronger than steel.”

But my need and desire to understand Holocaust survivors – their voices, their faces, and their passions – went well beyond my own family history.

In the summer of 1995, I joined together with almost 375 people from different religions, generations, nationalities, communities, and social and professional backgrounds at the Turning Point ’95 International Leadership Intensive held in Poland at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the extermination and labor camps that had been liberated fifty years earlier. Touring the camps with three survivors – two Jews and a communist resistance fighter – offered me a personal and concrete dimension to a tragedy that is still difficult to comprehend.

As a second-generation witness, I deeply sensed and identified with the horror and the pain. At the same time, I felt the hopes of those who not only suffered such horrendous events but who thrived in spite of them. It happened not just to THEM, but also to US! I came away with an important question: How can we learn from our experiences to prevent genocide?

The more I studied the Holocaust, the more closely I examined my own reactions to what I learned. I noted that these people – survivors, resisters, and rescuers – shared their extraordinary stories in the hope of creating meaning from their experiences and making a positive difference in the world. more...A trip to Israel in October 2002, at the height of the Second Intifada (Palestinian Uprising), helped me connect what I had learned about Holocaust survivors to what was happening now in Israel, Palestine, and the Middle-East. My husband and I chose to visit Israel for two weeks – a big step in those days of frequent terrorist bombings – in order to show our support for peace and to observe and experience first-hand what it was like to live with the threat of terrorism.

As I talked to family, friends, and new acquaintances and listened to government officials, tour guides, doctors, helping professionals and volunteers, and terrorism survivors, I observed the strength of the human spirit to cope with tragedy and uncertainty. Once again, I began to reflect upon my earlier question, as well as a new question: How can we move beyond the trauma of such an event?

To answer these questions, I knew I had to listen more. I wanted to understand and know the voices, faces, and passions of these otherwise ordinary people, this time those who experienced acts of terrorism and moved forward in their lives, creating meaning from their experiences and making a difference in the world. And so, I have taken on the difficult task of gathering and sharing their remarkable journeys in remembrance of the past and as a responsibility to the future. I hope these stories can shed a little light on someone else’s path through a dark period of their life. more... -

Why did you write this book and what did you hope to learn?

While, thankfully, most of us will never directly experience a terror attack, life crises are inevitable for most of us. I hoped that I and others would learn from these people how we too might be able to continue life with new vitality, purpose, insights, and productivity and how we might use this knowledge to successfully deal with our own life crises – and share it with others.

Recording and compiling these extraordinary stories into Living Beyond Terrorism brought me back full circle to my original interest. My hope was that this examination of the human impact of terror in Israel might bring about a greater understanding of important elements of our human experience and of the possibilities of overcoming trauma. I also hoped to explore what is in the stories of some individuals that allow them to move from some of the darkest experiences possible to make sense of their lives and move forward in their lives.

The book shares thirty-six compelling stories of hope and healing, as told by forty-eight survivors and families of survivors and victims of politically-motivated violence in Israel. The stories explore how these trauma survivors understand what has happened to them and the meaning they take away from their experience. The accounts vividly portray the feelings, thoughts, and actions of these individuals before, during, and after the attack – their suffering and losses, and more importantly, their hopes and dreams and the sources of their strength to survive.

As a researcher, not as a clinician or journalist, I was careful not to cross either of those lines but to document the stories as told in the voices of the survivors and families. As Henry Greenspan wrote in On Listening to Holocaust Survivors: Beyond Testimony (2010), “the sufficient reason to listen to survivors is to listen to survivors. No other purpose is required.” Just as some stories of Holocaust survivors tell of moving forward to extraordinary action, so have some of these otherwise ordinary people who personally experienced acts of terrorism shown that they too can prevail by the positive attitudes and perspective they adapt in the face of tragedy. And just as some Holocaust survivors found light in Nazi darkness, they too demonstrate the power to light up the darkness of terror, not allowing the terrorists to stop their way of life. more... -

Why did they want to tell their stories?

Many of those I spoke with asked me to share their stories to “help others face traumatic events” and “understand that there is life after trauma, and that life is not finished.” By telling and retelling their stories, we honor them and recognize the importance of their lives and the lives of their loved ones. By learning from their stories, we honor the importance of our own lives. And by telling their stories we bear witness. As so eloquently expressed by Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor, Nobel Poet Laureate, and Founding Chairman of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum at its dedication ceremonies, we must remember the past and our responsibility to the future: “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.”

We also “celebrate their lives” as people – as human beings – not simply as players in a larger story or as numbers. These testimonies help to personalize and contextualize historical events, humanize the people who have survived or perished, and establish real faces in the overwhelming sea of facts and statistics. Listening to their stories affords us historic memory and connection. As Chaim Potok wrote in Old Men at Midnight (2001): “Without stories there is nothing. Stories are the world’s memory. The past is erased without stories.” This is what we have learned about the importance of collecting the stories of survivors of the Holocaust; so too shall these stories of survivors of terrorism be a reminder to the world that there should never again be a world that could breed another holocaust for any people. more... -

Why do you still want to tell their stories?

Sharing these stories from the Second Intifada is still highly relevant and important ten or more years later. In Israel, every time the warning siren sounds or the Iron Dome leaps into action to intercept an incoming rocket ... or in New York when a bomber plans to leave a bomb in Times Square where 1600 children are watching The Lion King at a nearby theater . . . or in Boston when a bomb-laden package is left at the finish line of the Marathon, a sports event meant to celebrate human achievement and not to destroy existence, we must remember that at the end of the day, they are all victims of terror. It doesn’t make any difference that they were killed ten years ago or maybe two years ago, or in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, New York, or Boston. For the people who are left behind, it’s exactly the same thing . . . and for the world, it’s yet another example of man’s continuing inhumanity to mankind. more...

-

Did the book involve special research?

From a theoretical perspective, my work is inspired by Viktor Frankl, the noted neurologist, psychologist, and Holocaust survivor whose autobiographical Man's Search for Meaning documents how personal strength, wellness, and other positive outcomes can result from the struggle with a trauma or life crisis. Living Beyond Terrorism is grounded in humanistic and existential approaches, stressing the freedom to transcend suffering and the defiant power of the human spirit to make choices and embrace life. As expressed by Viktor Frankl in the opening quote to this book, “We must never forget that we may also find meaning in life even when confronted with a hopeless situation, when facing a fate that cannot be changed. For what then matters is to bear witness to the uniquely human potential at its best, which is to transform a personal tragedy into a triumph, to turn one’s predicament into a human achievement.” more...

My work is also influenced by the theoretical perspective of posttraumatic growth. Although the term is new, the idea that great good can come from great suffering is ancient, appearing in literature, philosophical inquiry, and religious thinking. The term posttraumatic growth was introduced by Lawrence Tedeschi and Richard Calhoun in the 1990s to refer to the positive psychological change experienced as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances. It describes the experience of individuals who have developed beyond their previous level of adaptation, psychological functioning, or life awareness.

Such positive changes can be manifested in several ways. While the encounter with a major life challenge may make us more aware of our vulnerability, it may also change our self-perception, as demonstrated in a greater sense of personal strength (we have been tested and survived the worst) and recognition of new possibilities or paths for one’s life. At the same time, we feel a greater connection to other people in general, particularly an increased sense of compassion for other persons who suffer; as a result we experience warmer, more intimate relationships with others. A changed sense of what is of most importance is one of the elements of a changed philosophy of life that individuals can experience as posttraumatic growth. A greater appreciation of life and for what we actually have and a changes sense of priorities of the central elements of life are common experiences of persons dealing with crisis. We may also experience changes in the existential, spiritual, or religious realms, reflecting a greater sense of purpose and meaning in life, greater satisfaction, and perhaps clarity with the answers to fundamental existential questions. Posttraumatic growth is about moving forward with action after an event of seismic proportion and entails the search for meaning and understanding the event’s significance in one’s life. more... -

How long have you been working on the book?

I began my doctoral studies in September 2000 and decided to examine the experiences of terror survivors after visiting Israel in October 2002 at the height of the Second Intifada. Between 2004 and 2010 I traveled to Israel eight times for extended stays to collect the stories that make up this book and which served to strengthen my belief in the incredible power of the human spirit.

The findings from this research, which was both interpretive and empirical, having qualitative data in the form of narratives or stories and quantitative data collection in the form of survey results, are documented in my doctoral dissertation “Finding Meaning and Growth in the Aftermath of Suffering: Israeli Civilian Survivors of Suicide Bombings and Other Attacks.” The findings were recently published in the peer-reviewed journal Traumatology. The article, "Themes of Resilience and Growth in Survivors of Politically Motivated Violence," provides the scholarly underpinnings and validation of my work, while the book presents the voices of the Israelis who live with and beyond terrorism. more... -

Who are the participants and when did you interview them?

The original dissertation research study sample included twenty-four Israelis, ages 22-63, who personally survived suicide bombings and other attacks on civilians between 2001 and 2003. Twenty-three of the participants were Jewish and one was a non-Jew who has lived in Israel for fifteen years and “feels more than Jewish.” The interviews were conducted in 2004, eleven to forty-four months after the attacks. The seven shooting incidents took place in or on the road to West Bank communities; the suicide bombings were in urban areas. Nineteen participants were personally injured in the attack; three lost a family member; and three were with relatives who were injured.

In 2004 I also collected testimonies from seventeen family members, bereaved family members, and military personnel injured in terror-related actions primarily during the Second Intifada. One story by a victim’s family from 1996 - between the Intifadas - is included because “for the people who are left behind, it’s exactly the same thing.”

In 2007 I revisited these individuals to probe for changes in levels of functioning and to learn the impact of the summer of 2006 Israel/Hezbollah/Lebanon War. Seven other Jewish survivors and bereaved family members were also interviewed. In addition, I interviewed fifteen Arab-Israelis - Christian, Muslim, and Druze - who also directly experienced the effects of terrorism.

In 2013, the individuals were requested to reflect upon and describe any important and meaningful changes that they might have experienced in their family, work, health, and/or outlook in life since the interviews.

In total, sixty-three people were interviewed. Living Beyond Terrorism shares thirty-six compelling stories of hope and healing, as told by forty-eight of these survivors and relatives of survivors and victims of political violence in Israel.

This book is a tribute to those who survived attacks, as well as the family members of those who perished. At the same time, it honors and recognizes the many helping organizations and people – governmental, non-profit, and medical – professional and volunteer – all of whom have provided loving care, services, and support to the survivors and their families. more... -

How did you find the people that you interviewed and was this a representative sample?

The people were recruited from the patients, clients, family, and friends nominated by contacts made in various communities in Israel. In addition, candidates were solicited via newspaper ads and by word of mouth. A few who were contacted decided not to participate because it might bring back unwanted memories that they did not wish to confront.

While this sample was neither random nor representative, it was reflective of those who chose to participate. The responses may or may not be generalizable to other countries and cultures as there may be some uniqueness to this population in the way that they have managed to live with the constant threat of terror. Although terror disrupts social and economic societal functions, there is evidence that the continuous threat of terror on Israeli civilians may have only marginal impact because individuals, families, and larger social groups have adapted their preparedness behaviors so as to minimize its impact. more... -

Why did you select a narrative approach to your research?

Again, although my role was as a researcher and not as a clinician and I was careful not to cross the line, there was a therapeutic aspect to the interview process. For survivors and family members, telling their stories repeatedly increases their self-awareness and understanding of their experiences and actions and helps them gain perspective on their lives and redefine their identity. Their narratives help them rebuild coherence in their lives, giving order, structure, and meaning to their experiences, as well as a beginning, a middle, and an end to their stories.

Furthermore, recovery is supported by disclosing their personal narratives to interested and supportive listeners - including family, friends, other traumatized people, professionals, general audiences, and the author. As a witness to their stories and as a researcher with a positive being and a lens of positive outcomes, wellness, growth, and thriving, I was able to provide emotional understanding and affirmation. The process was healing and meaningful for the storytellers - and for me as well. Our paths have touched and we have been strengthened and enlightened by each other. more... -

What conclusions do you draw? Do they support or challenge generally accepted views in your field?

Although we cannot draw conclusions from these findings, the stories provide answers to some very important questions: How do the Israeli survivors and families of survivors and victims live with the constant threat of terrorism and the social and economic disruption of their lives? How do they develop coping skills and adapt to their situation? What do these changes look like and how are they manifested? What accounts for the fact that so many of them did as well as they did? Was their recovery due to certain pre-trauma personality traits and inner resources and/or to their post-trauma environment - their families, their communities, and the organizations with which they had contact?

In the media, we hear and read a lot about posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) which may occur in a person who has faced traumatic events and which focuses on negative outcomes and illness. This book comes from a perspective of resilience and posttraumatic growth that focuses on positive outcomes and wellness and describes the phenomena of bouncing back and moving forward, sometimes to extraordinary action. The stories in this volume reflect several possible patterns of change or responses to the trauma of terror acts, ranging from those who survive with impairment (as in posttraumatic stress), to those who bounce back after experiencing hardship and adversity and move on with life as usual (as in recovery or resilience), to those who move forward, surpassing what was present before the event occurred (as in posttraumatic growth, growth following adversity, or thriving). The experiences described in Living Beyond Terrorism support the view that personal distress and growth often do coexist and that it is the individual’s struggle with the aftermath of trauma that enables positive psychological change.

All of the people in this book have struggled with highly challenging life circumstances—the traumatic experience of a terror act against civilians. As we read these inspiring stories of finding meaning and growth in the aftermath of suffering, we can learn how these individuals live next to and move forward with their feelings of grief, pain, and helplessness, overcoming suffering and moving forward from terror to hope and optimism and from grief to meaning and healing. There are some common themes that evolved from these stories – ones that can be cultivated to master any crisis. These include:

◦ Struggling, confronting, and ultimately integrating painful thoughts and emotions

◦ Adjusting future expectations to fit the new reality and focusing on the important things in life

◦ Calling on inner strength, core beliefs, and values

◦ Staying in control and not falling apart

◦ Moving forward with strength gained from past experiences and prior adversity

◦ Grappling with fundamental existential questions through religion and spirituality

◦ Staying healthy and focusing on body image

◦ Finding the silver lining and creatively giving back—moving forward with action

◦ Staying connected and seeking outside resources to help survive rough times

◦ Telling their stories and making sense of their lives

◦ Being hopeful, optimistic, and celebrating life

◦ Discovering who they are more... -

Is there a recipe for ensuring positive change, resilience, and growth?

There is no one recipe – no right or wrong response – about how humans respond after struggling with horrific experiences. Every individual experiences a traumatic event, ascribes meaning to it, and takes action as a result of their personal characteristics, past experiences, present context, and physiological state. While there is no single factor or magical combination that ensures a positive outcome, certain psychosocial, social, and spiritual factors have been shown to enhance stress resilience and growth. Some may be internal factors, such as optimism, hope, self-confidence, hardiness, sense of coherence, flexibility, creativity, humor, acceptance, religious beliefs and spirituality, altruism, exercise, and the steeling effect of having weathered the storm of prior traumas. Other enabling factors may be external, especially the support of friends, family, other traumatized people, and professionals, as well as the broader society and culture. more...

-

How do the survivors, their families, and the families of the bereaved move beyond the trauma of such an event?

They are creative, find the silver lining and give back, moving forward with action. Many survivors find meaning by their deeds, experiences, and the attitudes they take towards unavoidable suffering, acknowledging the human potential to grow. They may find meaning by creating a work or by doing a deed. Some construct meaning through self-transcendence or altruism. They see negative events as an opportunity to help others, contributing to society and turning tragedy into action or activism.

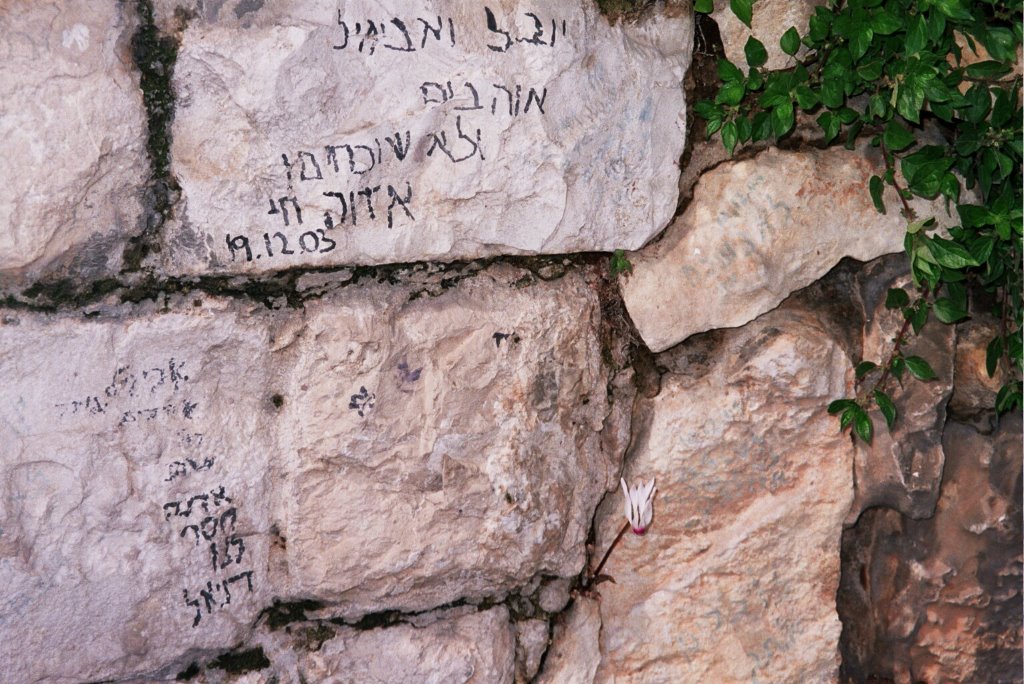

In the wake of grief, many bereaved family members also create meaning through altruism; others create memorials to meaningfully recognize and honor their loved ones. There are different types of commemoration. Some may be spontaneous, as in the placing of flowers, pictures, and memorial candles at the site of an attack, or in the handwritten messages of love and remembrance painted on nearby stone walls, as shown in the photograph on the back cover of the book. In the photograph of the spontaneous memorial created on Moriah Boulevard in Haifa near the site of the Bus #37 attack, small flowers push up through the cracks – symbolizing rebirth and new growth. Later, the family and friends of the person who died may design and fund private commemoration at the place of the attack, in schools or playgrounds, on the internet, in the synagogues, and elsewhere, allowing people who never met the fallen to know something about them and, more importantly, to remember them. Finally, public municipal and state commemoration allows the society as a whole to mourn and remember, for example at the national cemetery at Mount Herzl in Jerusalem on Yom Hazikaron (Israel’s national memorial day for the fallen soldiers and the victims of terror). more... -

Why do you use the term survivor, not victim, of terror?

The use of the term survivor sometimes is controversial within Jewish circles; there are some who feel that “survivor” should be used only for those who have survived the Holocaust and not those who have survived terror acts. Although the terms victim and survivor are often used interchangeably, the terms victim, survivor, thriver, and even victor do reflect attitudinal distinctions, as we hear in the self-identities expressed by many of the speakers in these stories.

-

Why do you use different terms for the attacks, e.g. politically motivated violence and terrorism?

I am sensitive to the fact that the topic at hand involves, at least, two subjective histories that are often highly politicized. My goal is to present these matters objectively in a non-political manner. Above all, this book is about people - how they feel and think and act while struggling with horrific experiences - not about politics. Nonetheless, some may question how I use the terms politically motivated violence or political violence to describe the incidents in this book, or how and when I use the words terror or terrorism. Wherever possible, I use the actual words of the speaker or writer being quoted, such as the Hebrew word for an attack – piguah or piguim (plural) – or a more event-specific term - suicide bombing, shooting, or rocket attack. But the words terror, terror attacks, or terrorism are the best terms to use as this is how it is commonly understood, or because the terms best explain the psychological impact on the survivors of these events when describing the psychological aftermath of these events. more...

-

Is there a difference between Jewish and Arab responses to terrorism?

Again, this book is not about politics, it is about people – how they feel and think and act after struggling with horrific experiences. The human impact and responses are similar for all victims of indiscriminate terrorist attacks or politically motivated violence, in which the actual victims are irrelevant to the perpetrators. As a result, every individual is instilled with the fear that the next attack may strike them or their loved one. Terrorism erodes - at both the individual level and the community level - the sense of security and safety people usually feel and challenges the natural need of humans to see the world as predictable, orderly, and controllable.

There is a range of responses. Some people cope successfully with difficult situations, recovering within a short period of time and functioning normally. A minority of people, however, experience difficulties that linger and disrupt their ability to function at home or work. There also is a wide range of ways to cope. At one extreme, some people become numb to constant stress and avoid current events and news coverage. At the opposite extreme, others follow the news closely, hyper-vigilant, letting the odds of an attack direct their every move.

For the Jewish-Israelis, there has been unique exposure to and memories of other lifespan traumas, e.g. pogroms, persecutions, wars, and ultimately the Holocaust.

While Arab-Israelis also suffer from PTSD and feelings of vulnerability and helplessness, there are additional stressors. On the one hand Palestinian Arabs are living in Israel in a society that is closely identified with western values. Many find it difficult to hold on to the Arab traditions, beliefs and perceptions that have defined them. Furthermore, some Palestinian Arabs in Israel feel a conflict of dual identity and dual allegiance as both Israeli and Palestinian. Thus, they feel the pain of being attacked by other Arabs, who are their brothers rather than by people seen as an external or natural enemy. In addition they themselves are under attack and experiencing a life threatening situation, like the rest of the Israeli people. more... -

Why do they stay and how can they put their children’s lives at risk?

For Jewish Israelis, the State of Israel was founded as a homeland for the Jewish people, representing “the hope of two thousand years, to be a free nation in our land, the land of Zion and Jerusalem,” as expressed in Hatikvah - the Hope - Israel’s national anthem. As Daniel Gordis writes in Saving Israel: How the Jewish People Can Win a War That May Never End (2009), “It was hope that Israel restored to the Jews; and it is hope that would be utterly lost if Israel ever succumbed.” And it is this hope that drives Israelis to live in Israel and raise their children in a Jewish homeland, in spite of their fear of terrorism. “It’s the lifestyle. It’s the habits. It’s the culture.” And, in the end, “It is the safest place in view of all the anti-semitism in the world, which is so close to what you hear about the Holocaust.” more...

For many of the Arab-Israelis as well, Israel is home. “This is my house and my family. How can I leave Haifa, the nicest place in the world?” more... -

Why did you choose to do this difficult work in Israel?

My upbringing instilled in me important values and passions. My parents, Emanuel and Dina (Wirshup) Dauber z”l, had emigrated to Palestine as teenagers with their families in 1934 from Brooklyn, New York and Vilna, Lithuania. They met and married in Jerusalem and since have returned there to their final resting places on the Mount of Olives. My brother Eddie and I were raised in a Jewish and Zionist home in New Jersey, surrounded by our parents’ love of Israel, Jewish education, charity, family, and friends. Growing up, Israel was always home in our hearts, with trips back and forth to visit family in Israel or in our home.

When asked why I have chosen to do this difficult work in Israel – so far from home and my husband, two married sons, and four grandchildren – when there were other opportunities for study in the United States, such as survivors of 9/11, I respond that “My heart and passions are in Israel. This is where I am committed to making a difference. My love for the people in Israel lets me live like they do - to live in the moment and not worry about the situation and what might happen. You never know. When you’re so passionate about something, you just keep doing it.” more... -

How and why did you make such a seemingly extreme change in career from the automotive

industry to human development?

My early life prepared me for a lifetime of non-traditional roles. I earned an A.B. degree in Chemistry and a Master of Science degree in Pharmaceutical Chemistry. I retired in 2001 after nearly twenty-five years of service in the automotive industry with Chrysler Corporation, where I held numerous supervisory, management, and executive positions in planning, operations, and marketing within the Mopar Parts Division – usually the first woman to have held these positions and always nudging the glass ceiling upwards.

My career progression from Pharmaceutical Chemist to Automotive Executive was nontraditional and evolved through the application of my strong analytical, problem-solving, communication, and interpersonal skills to each new situation. I was known as a strategic thinker and for my ability to bring about positive changes in the organization, its people, its culture, and its processes. And I always thought of my work as helping people – helping to nurture them and improve their processes and their lives, by modeling the behaviors necessary for success.

When I retired, I decided that the next stop on my life path journey would be to feed my passions for learning, intellectual stimulation, making things better, and helping people – this time by helping people who had survived terror attacks and other challenging life crises make sense of their experiences and live healthy and fulfilling lives. more...